Could Legalizing Mid-Rise Single-Stair Housing Expand and Improve Housing Supply?

There is widespread agreement that an insufficient supply of new homes has contributed to our housing affordability challenges in recent years. This recognition has led to efforts across the country to reform zoning regulations to allow for higher density housing as a means of encouraging the development of both more units and housing that is more affordable due to better use of land. While zoning reform is an important element of any strategy to increase housing supply, often overlooked in policy discussions is the way in which building codes make it difficult to develop more affordable, appealing housing types.

One element of the building code that is receiving increasing attention is the requirement for more than one means of egress (stairs) in buildings that are over three stories and have more than twelve units, as required in Massachusetts (and there are similar restrictions in most of the US). In a new report released today, Legalizing Mid-Rise Single-Stair Housing in Massachusetts, conducted by the design firm Utile in partnership with the Center and Boston Indicators, this element of the building code is examined from an architectural perspective to illustrate how relaxing this requirement to allow mid-rise (up to six story) buildings that rely on a single-stair could unlock opportunities not just for more housing, but more appealing types of homes that would fit well within the existing urban fabric.

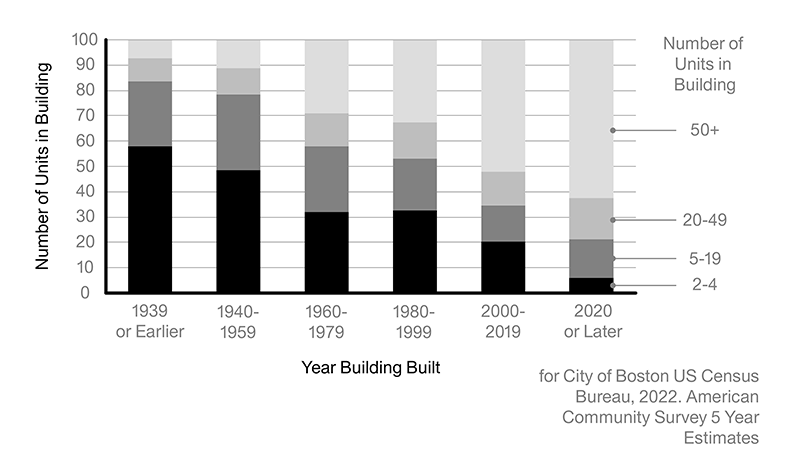

In fact, mid-scale housing has long been an important part of the housing stock in the Boston area, with buildings of between 5 and 19 units accounting for more than a quarter of homes built prior to 1980 but only about 15 percent since then (Figure 1).

Figure 1: share of Total Housing Production by Building Unit Count (as a share of all units built per year)

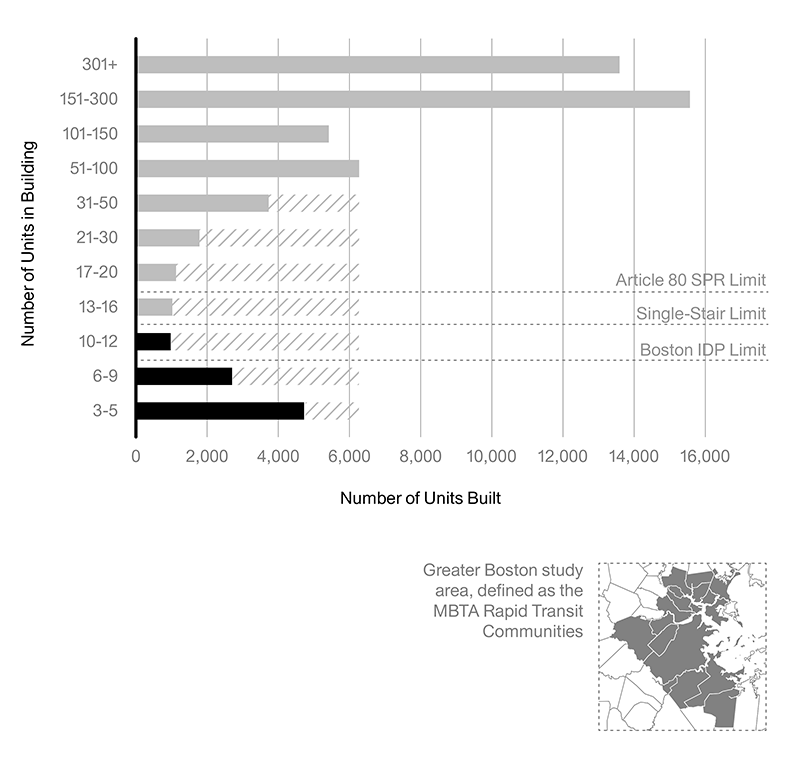

In recent years, new multifamily construction of buildings with between 10 and 30 units has been sparse in greater Boston, and has heavily skewed toward buildings with over 100 units (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Total housing units built in Greater Boston by Number of Units in the Building

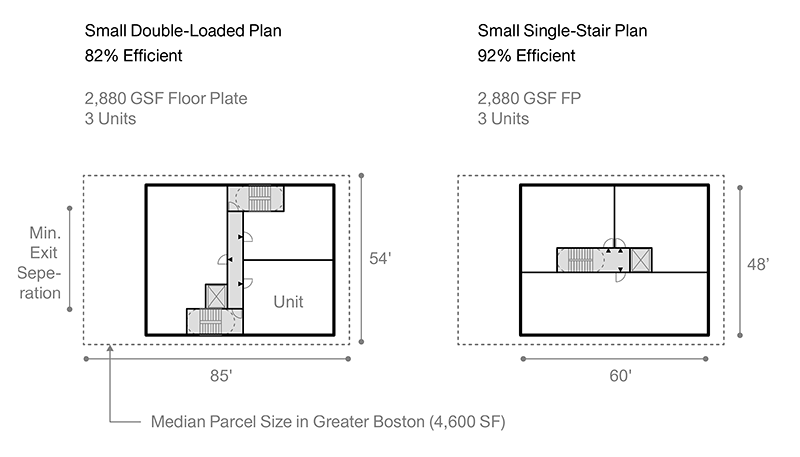

The homes would also have improved access to light and air as eliminating the need for a central corridor allows for units that have windows on more than one side of the building, which provides both cross ventilation and direct sunlight throughout the day (Figure 3). By eliminating the need for a second staircase, the buildings also have a higher efficiency ratio (the share of interior space that is rentable) which makes them more financially feasible. The scale of these buildings, and the single stairway, also promotes greater neighborliness than afforded by a long anonymous corridor.

FIGURE 3: EFFICIENCY OF DOUBLE-LOADED VS. SINGLE-STAIR PLANS

The report proposes that Massachusetts modify its building code to allow for single-stair buildings of up to six stories and 24 units. This recommendation, however, is mindful of the safety concerns that gave rise to the double-egress standard, and provides residents with reduced floor plates that shorten fire escape routes down to 75 feet from 125 feet in double-stair buildings. Since the number of units in the building is lower, the number of residents using the stairwell would also be much lower. The proposal also increases the fire rating of entry doors while maintaining the use of sprinklers, fire-wall ratings on stairwells, and other existing fire protections. As the report documents, much of the world allows single-stair building of larger sizes without an increase in fire deaths so there is good reason to believe that it is possible to ease the current restrictions without risking safety.

Obviously, changing the building code must be approached with appropriate scrutiny to ensure that an adequate level of safety is maintained. But with housing supply constrained, particularly for smaller buildings, it is important that building codes be revisited to ensure that we are not precluding the development of much-needed housing with an overly cautious approach. Hopefully, the report will help spur the inquiry not just for single-stair limitations but for such other issues as the maximum height of mid-rise buildings and the use of exterior stairways.